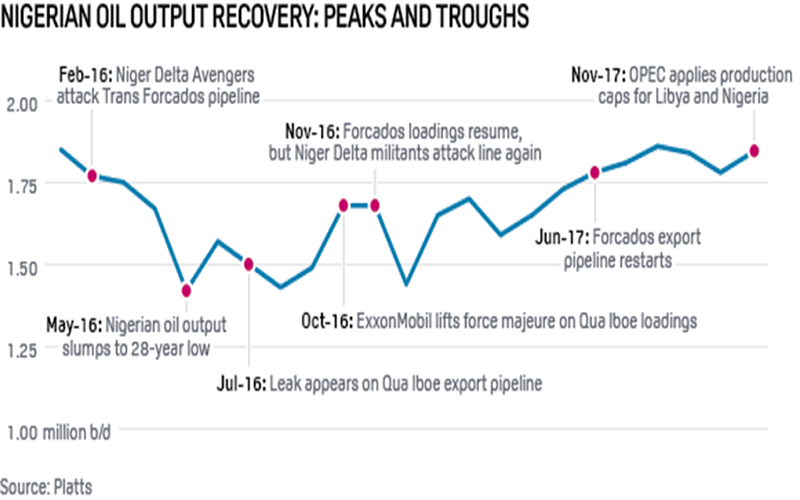

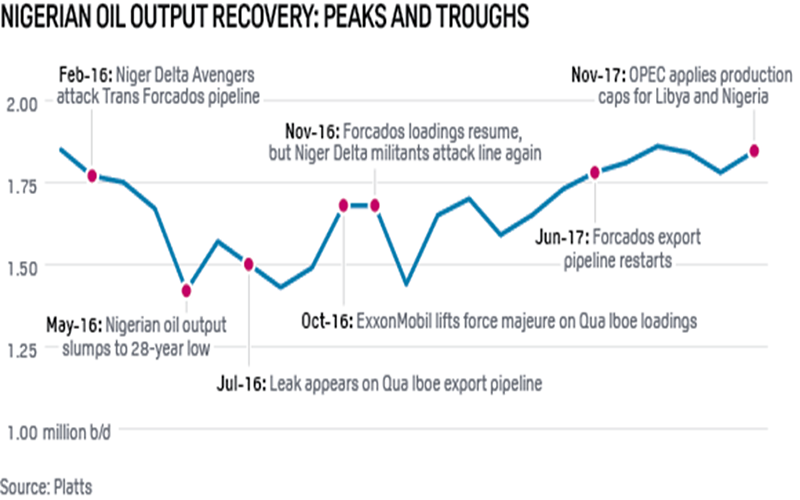

The West African country’s crude production has been languishing at only two-thirds of its full capacity this year due to these factors along with its obligations under the OPEC+ production cuts.

And, with further fiscal and security uncertainties ahead, the outlook for the country’s oil sector is likely to come under pressure despite the implementation of some reforms, they added.

Nigeria has the capacity to produce around 2.2 million-2.3 million b/d of crude and condensate, but production has averaged around 1.64 million b/d so far in 2021, according to S&P Global Platts estimates.

In the last six months, many of its large oil fields especially those in the Niger Delta like Forcados, Bonny, Escravos, Brass River and Qua Iboe and some offshore fields like Bonga, Usan, EA, have been pumping much below their normal levels due to either technical or maintenance issues.

There has also been a rise in leakages at some of the country’s key pipeline networks. Some of these were because of an increase in pipeline sabotage while others are because of the country’s fragile and aging infrastructure, some of which need urgent rehabilitation work.

In April and May, there were shut-ins by some of the producers using the Nembe Creek Trunk Line to transport their production to Bonny Terminal, due to a couple of leakages on the line, according to an official from the Nigerian petroleum ministry.

“Maintenance repairs on the Trans Ramos Pipeline, leading to production shut-ins by producers using this pipeline, also affected Forcados terminal’s production,” the official said. “There was also maintenance at Bonga, as well as pipeline maintenance and repairs at Escravos, resulting in underperformance.”

Qua Iboe output took a hit in December due to an issue at its terminal, which led to a one-month halt in its crude loadings. While the EA oil field is currently undergoing maintenance work at its offshore terminal, sources added.

Security, fiscal risks

The country’s production growth is also threatened by fiscal stress and the lack of regulatory reforms.

The rise of kidnappings and other security threats in the oil-producing south are also expected to deter investment.

S&P Global Analytics revised down its crude supply forecast for the second half of 2021 by around 130,000 b/d to 1.8 million b/d.

Nigerian crude loadings have been “showing consistently lower volumes on recent pipeline issues,” and with “violence rising in the southeast” of the country, downside risks are growing,

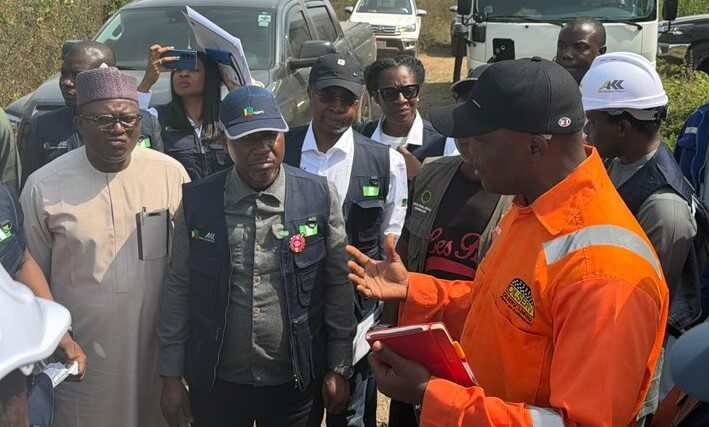

Africa’s largest oil producer is just starting to take steps to sweeten its relations with international oil companies in a bid to stem its recent output decline.

State-owned Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation recently signed a deal with its partners in the deepwater oil block OML 118, clearing the path to a major expansion of the country’s Bonga oil and gas field.

But international oil companies are urging the government to urgently pass the landmark energy legislation — the Petroleum Industry Bill — into law, which would send a strong signal to investors of more predictability.

The PIB is expected to be passed by parliament sometime in H2 2021, government sources said.

This key legislation, which is meant to completely overhaul the Nigerian oil industry and provide new fiscal incentives to producers, has been in the works for more than a decade.

Under the latest OPEC+ deal, Nigeria has been allowed to increase crude production to 1.535 million b/d and 1.554 million b/d in May and June, respectively. For July, its quota will rise to 1.579 million b/d.

Transition backlash

The NZE2020 model will ratchet up pressure on integrated oil majors to decarbonize faster and drive more investment dollars into renewable energy. While the IEA’s bill for a faster energy decarbonization will double to $5 trillion a year, upstream spending will shrink more than threefold in the coming decades.

European integrated oil majors such as BP and Shell have already started shedding upstream assets under their pivot to lower-carbon, renewable energy. ExxonMobil’s recent loss of board seats to activist hedge funds suggests US Big Oil could soon start moving in the same direction.

But as Western energy majors accelerate upstream divestments, it’s unclear how much of their oil and gas resources will simply be transferred to smaller, private companies and state-run national oil champions less exposed to climate scrutiny. An unintended consequence of this process will be more oil resources being operated by companies “almost certainly dirtier” than the original IOCs owners, according to Christof Ruhl, BP’s former chief economist.

“This is a warning sign, if it proceeds, that will lead to a concentration of oil investments away from IOCs and shale to the OPEC and NOC countries which do not face these kinds of restrictions,” Ruhl recently told Gulf Intelligence.

State oil giants such as ADNOC, Saudi Aramco and China’s CNOOC and PetroChina have already announced either higher capital budgets or upstream expansion plans since the start of the pandermic.

With the Middle East’s OPEC producers also dominating the world’s supplies of low-cost, low-carbon crude, a more powerful producer cartel also could spell higher future prices, he said.

Ruhl, currently the senior research scholar for global energy policy at Columbia University, also sees the potential for investors to start shunning green energy players if they are concerned over earnings from lower-margin green power investments.

“Expect some kind of backlash against this energy transition because investors will not stupidly run into ESG funds if they see there is trouble on the horizon … that we don’t have enough oil,” he said.

Carbon capture

But with the total production from the six top IOCs at around 13 million b/d, or about 13% of pre-pandemic global production, the risk of any sudden collapse in global supplies is unlikely, according to S&P Global Platts Analytics. Indeed, even if the production from the world’s biggest IOCs were to go to zero, oil supplies would still need to contract by another 28 million b/d by 2050 under Platts Analytics’ scenario to meet a less-ambitious 2-degree global warming target.

The trajectory of oil supplies in a net-zero world will also depend heavily on carbon prices from either carbon taxes or emissions trading schemes.

Many oil companies are banking on large-scale, commercial carbon capture and storage (CCS) plants to keep their cleanest barrels flowing while hitting net-zero targets. With Western energy majors at the forefront of commercial-scale CCS, higher carbon prices and lower abatement costs may be key to their future supply role.

Bank of America estimates the carbon cost of keeping all fossil fuels below ground at around $200/mt, well above the implied carbon costs reflected in IOCs’ share prices.

Energy Transition at the speed and scale of NZE2030 may be more than just a tough challenge. Russia’s energy minister has warned of skyrocketing future oil prices due to an impending supply crunch as producers ditch fossil fuels.

Oil industry reservations over the path to net-zero don’t bode well for its achievability. As the IEA notes, any delays to slashing emissions today effectively kicks net-zero by 2050 out of reach.