The message from this year’s Africa Oil Week and African Energy Week, held back to back in Cape Town, could not have been clearer. With energy poverty endemic and war in Ukraine driving home the importance of affordable and secure energy supply, the continent must fully develop its abundant oil and gas resources.

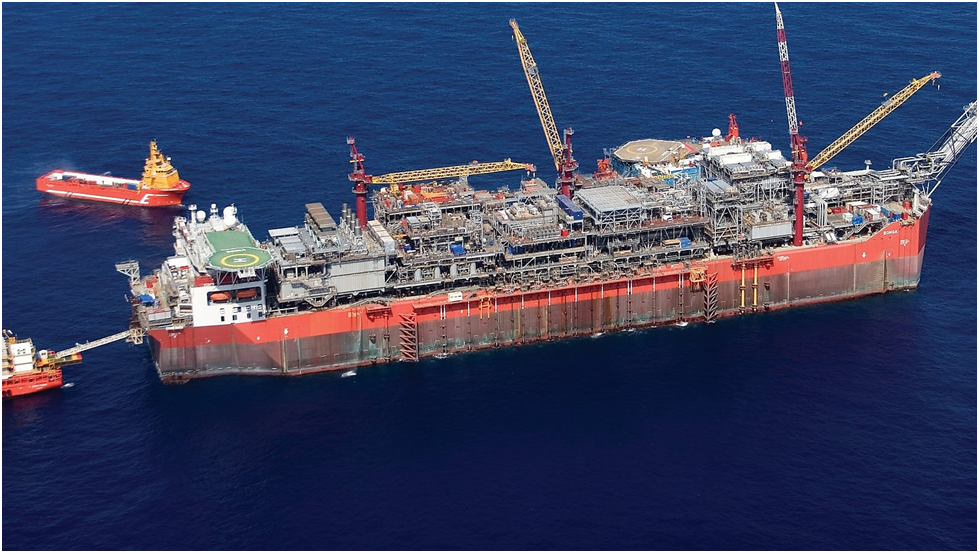

Big Oil’s huge deep and ultra-deepwater discoveries are driving Africa’s upstream resurgence, including Baleine (Eni) in Côte d’Ivoire and Venus (TotalEnergies) and Graff (Shell) in Namibia. But local E&Ps must step up to develop the region’s enticing shallow-water and onshore resources to maximise the opportunity. And there is the rub: whereas the Majors can readily self-finance and access low-cost debt, it is a different story altogether for much of the rest of Africa’s upstream sector.

How can Africa finance its oil and gas riches? Mansur Mohammed, Head of West Africa Upstream Research, is on the ground in Cape Town.

Better projects make for better finance

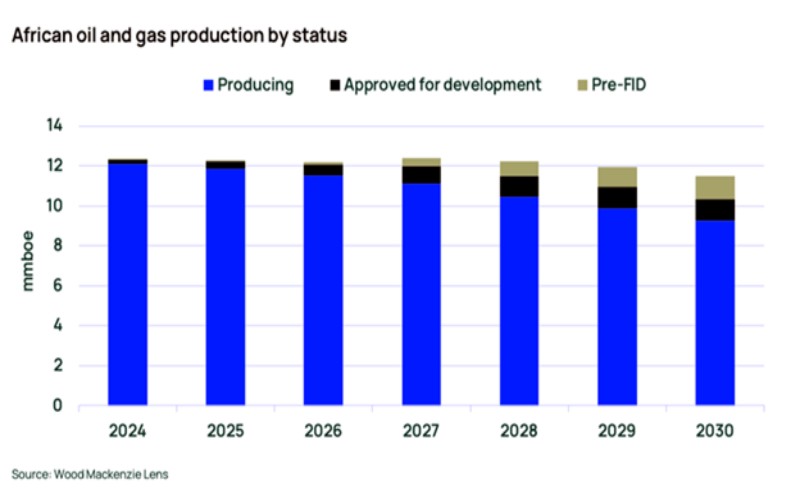

High-quality projects in Africa continue to move ahead. We expect 2023 to be a significant year for new production start-ups and African greenfield FIDs are also moving forward. Four major greenfield projects could reach FID this year, with Angola to the fore.

Much of this is inevitably being led by the Majors. With bulging balance sheets and options to debt finance, divest assets or sell down equity positions to fund African projects, capital is not a barrier to growth.

African governments are pivotal to financing

African governments are critical to the ability to secure financing for oil and gas. Several African countries offer progressive sliding-scale profit share, royalty and tax rates, which enable faster cost recovery – a key issue for financiers. Terms that provide for accelerated depreciation of capital for cost recovery and tax purposes – and the widening of ring fences to allow producers to consolidate investment in new areas with revenue from existing areas – also help. Egypt is a good example.

In two of Africa’s major resource holders, we also see ongoing efforts to crowd-in funding. Nigeria’s new President Tinubu has signalled a significant shift in fiscal and monetary policy to boost investment with a focus on the oil and gas industry. Meanwhile in Angola, improved upstream terms have been negotiated on an ad-hoc basis for several licences and helped to unlock exploration and development spending.

Governments can also support the flow of capital for African M&A deals by fast-tracking regulatory approvals. Holding up investment on mature assets only accelerates production decline rates.

With smaller balance sheets and tightening lending criteria from banks, independents and local players across Africa do not have this optionality. To have any hope of accessing capital, quality matters. Companies must push hard to reduce costs, improve project delivery timelines and ensure watertight ESG credentials including carbon emissions. Without this, lenders will remain thin on the ground.

Opening more innovative sources of finance

‘Peak ESG’ may have been 2021, but Africa remains at the sharp end of the squeeze on oil and gas funding from traditional lenders. With a clear stratification between the Majors and African E&Ps, the latter must look to more innovative sources of finance.

Firstly, we expect more activity from Africa-focused banks as international banks continue their retreat. These banks – ambitiously – believe they can finance up to a third of the oil and gas investment needed in Africa, providing greater liquidity when lending in local currency.

Secondly, the role of traders offering production-based financing is growing in importance. Identifying a gap in the market almost a decade ago, traders are now underwriting significant debt for indigenous Nigerian players, moving at speeds commercial banks are unable to match. But traders must also service their own debt, increasing lending costs to third parties. Typically, only the highest-value barrels make the cut.

Finally, there remains some scope for multilateral lenders and development finance institutions (DFIs) to finance projects in Africa that tie into local infrastructure and industrial development. However, most remain hesitant to directly finance upstream supply. More positively, the African Export-Import Bank last year reached agreement with the African Petroleum Producers Organization to create the African Energy Bank, a signal of intent by the continent to find viable sources of funding for its oil and gas projects.

Africa rising

The ambitions of COP28 are a timely reminder that the world cannot wait forever for Africa to develop its oil and gas riches. But there is a golden opportunity for resource-rich African countries to tap into the world’s need for energy security and tackle energy poverty at home. Attracting finance is the Achilles heel, and governments and willing financiers must leave no stone unturned to ensure that local companies are able to play their part.